Quodlibet XLI, 2014 [oil paint on canvas]

I can’t believe I forgot to upload this one! This is my review of Tate Liverpool’s 2021 Lucy McKenzie Exhibition for Issue 118 of Bido Lito! I also had the fabulous opportunity to interview Tamar Hemmes, an Assistant Curator at Tate Liverpool, and get her thoughts on McKenzie and her incredible work. Enjoy…

If I were to slice the roof off of Tate Liverpool, leaving me with the most fascinating birds eye view of Lucy McKenzie’s exhibition, it would be like looking at a patchwork quilt of over twenty years worth of her work; a loud, can’t-quite-take-your-eyes-off-it quilt, incorporating various punky squares of juxtaposing material, themes and skill, weaved together with the same political thread throughout.

Showcasing 80 works of the Glasgow-born, Brussels-based multimedia artist, Tate Liverpool can take the crown for presenting the largest UK retrospective of McKenzie’s work to date. The viewer can expect all of their creative tastebuds to be tingling, faced unapologetically with hyperrealistic architectural paintings, illusionistic trompe l’oeil exercises, fashion items and even furniture the artist designed herself for Nova Popularna, her very own artist’s salon back in 2003.

Expect art in unexpected places: on ceilings, on mannequins, TV screens, panning across several walls, placed in glass boxes and more. Not only does the exhibition reject any sort of familiar white cube aesthetic, but it will undoubtedly satisfy the most diverse of artistic appetites.

Walking through the exhibition, every corner and section of artwork is screaming out about the immense skill of this artist. Each room takes on a new element to show off her talent across numerous practices. In conversation with curator Tamar Hemmes, she explains McKenzie’s capabilities stating: “Lucy actually went to a school of decorative painting when she was already an established artist, just to become a better painter and that’s what you see when you first encounter these works.” The illusionistic trompe l’oeil paintings are evidently a product of this further education, because the detail is startlingly sublime. Quodlibet XIII (Janette Murray) (2011) was the first of these works that my eyes stumbled upon, causing me to look like I was dancing as I walked backwards, forwards and circulating the circumference of the canvas to justify in my mind that I wasn’t actually viewing something three-dimensional. Doubting the judgement of my own vision, these intrinsically detailed paintings stirred a vulnerability within me, like I was inferior to them. That makes for an incredibly powerful display of artwork.

Alongside a dedicated space to replicate nostalgic scenes from Nova Popularna, McKenzie’s fashion label Atelier E.B also earns some space for display, with some items even for sale. This partnership with the designer Beca Lipscombe, exploring fashion research, commercial display and exhibition design, has made her interests even more expansive, and demonstrates the more collaborative side of her work which is seemingly a recurrent theme. “She dips into bits of history and looks at the work of different artists and different architects and designers. It’s a way of using existing imagery rather than inventing her own and reevaluating or re-examining it.” This is exemplified explicitly in the second room of the exhibition, where an array of work is presented focusing on mass media representations of athletes in the Olympic Games. More specifically, the oil painting Curious (1998) depicts a runner bent over in the starting blocks, highlighting the eroticisation of female athletes in popular media.

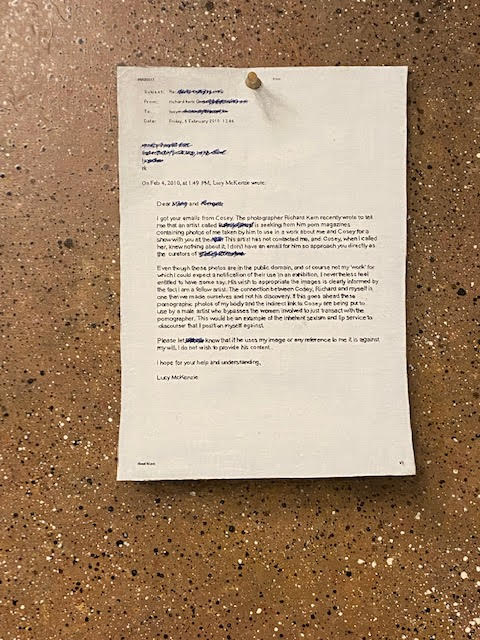

This feminist undercurrent runs throughout the gallery space, particularly towards McKenzie’s later works which become slightly more autobiographical; documenting a real incident, the 2013 painting Quodlibet XXVI (Self-portrait) incorporates a letter addressed to a list of curators and artists who wanted to use pornographic pictures of McKenzie during the 1990s for an exhibition without her permission. Through the exposition of such an attempt, which would have undoubtedly been preferred to have been kept quiet, McKenzie successfully holds on to her power as a woman and presents further commentary on the gender politics within the artsworld, as well as producing a really beautiful painting.

On the surface, the display doesn’t make a lot of sense. There’s no order, no sense of chronology; easy categorisation is certainly a foreign term, but I, somehow, didn’t feel the need to question it, nor did I want to. Hemmes talks about this in more detail: “The works all sort of interact in a way where you can see different connections in different rooms” before enlightening me to the fact that McKenzie quite playfully tends to depict some of her pieces in later works (Glasgow, 1938-1966, 2017 in Rebecca, 2019). For a gallery space to hold so many contrasting ideologies, materials and artforms, it’s quite enchanting to experience the sense that each work has every right to be there, threaded across to one another like an erratic corkboard in one of those Netflix murder mysteries. It certainly seems that the more you interrogate this exhibition and Lucy McKenzie’s work in general, the more layers that fold out effortlessly in front of your eyes, whether you spot them at first or not.

Sadly the exhibition ended earlier this year, but feel free to look at McKenzie’s work through the Tate website: https://www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-liverpool/lucy-mckenzie or the artist’s website: https://lucymckenzie.com/

![Eeek! I know I’m probably supposed to remain super professional (whatever that means) and all cool and chill about these things but I’m SO excited to share Totality, the second exhibition I’ve worked on but the first show I am solo curating! Exhibiting 3 incredible artists, Elina Yumasheva, Aiming Wang and Kelvin Wong, we want to show you that it IS possible to create fabulous temporary exhibitions in the most sustainable, eco-friendly ways through three very different types of visual practice, and exhibition-making by recognising how truly interconnected we are with the natural environments that surround us.

You can catch us for one day, and one day only next Tuesday (12th) from 10am-5pm, where we will all be present to engage in some thoughtful, considerate (and fun!) conversations around this topic outside of the Studio Building at Battersea Campus 🤍🌿🌎

[Poster made by yours truly]](https://www.confessionsofanartjunkie.com/wp-content/plugins/instagram-feed/img/placeholder.png)